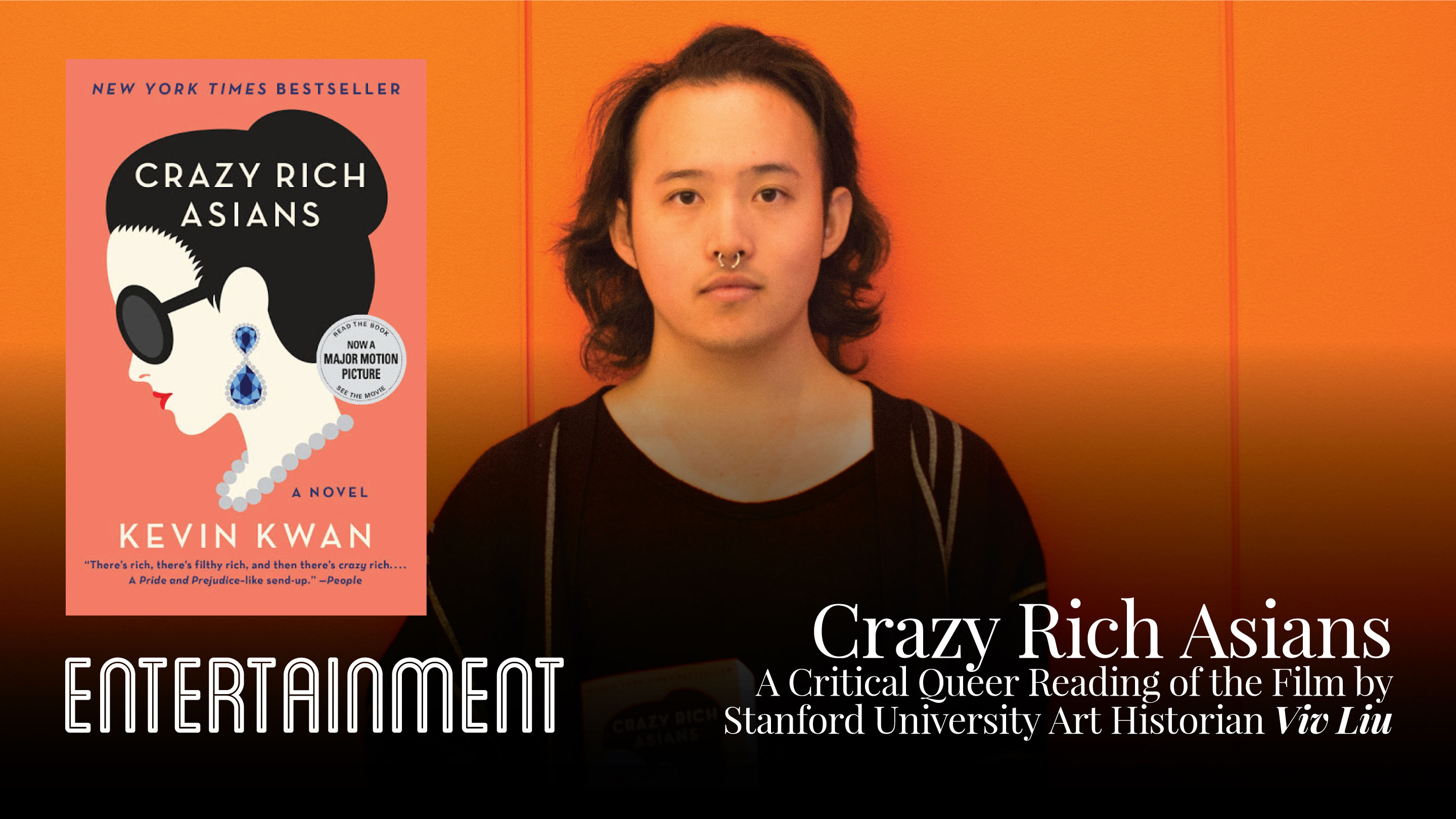

ENTERTAINMENT

Crazy Rich Asians

A Critical Queer Reading of the Film by Stanford University Art Historian Viv Liu

■ INTERVIEW BY THOMAS SUH PHOTOS BY DOMINICK HILDEBRAND & KATHY HUTCHINS (SHUTTERSTOCK.COM)

Crazy Rich Asians (CRA) is the first movie in 25 years since Joy Luck Club to star a majority Asian cast in a major Hollywood film. This film has grossed more than $238 million worldwide–making CRA the top grossing romantic comedy in 10 years. The overall success of the movie has been seen as an indication that audiences are hungry to see more POC-centered films coming out of Hollywood.

Crazy Rich Asians cast at the Hollywood Film Awards 2018 in Beverly Hills. Photo: Kathy Hutchins/Shutterstock.com

Even though CRA is largely a straight romance comedy, what personally drove you to see this film?

It was the representational angle, in which the movie was framed. What drove me to see the movie was out of an obligation as part of my Asian American Citizenship and identity. After watching the film, Crazy Rich Asians continued to occupy my mind as a source of constructive conversations relevant to queer people of color.

This does bring up the question of how to prioritize your identities, I’ve always been very adamant that I choose my racial identity, because of the ways that mainstream queer narrative is inherently so racist. In a way, it feels more achievable and comfortable to stick to POCs, than it does to a queer community-because anti-queer biases in communities of color is the result of white supremacy and imperialism. It feels like a smaller hurdle or gap to bridge, or at least a source of greater power to combat these structures.

Let’s talk about the way the film presented Asian men and the Asian male body. Why is the film’s depiction of the Asian male body as sexually desirable and visually accessible, particularly important to the queer male gaze and for POCs–particularly Queer Asian men? Did the film do an effective job of disrupting negative constructions of Asian male sexuality in mainstream media?

I think the moments when I saw desirable Asian male bodies are when my queer gaze was able to penetrate. But what the film was presenting was very respectable, assimilating into a norm of what is hegemonically attractive. There is a particular reason as to why they chose these men assimilable into the Western, masculine beauty norm. Also, I think it’s no mistake that the actor who plays Nick Young is half-white British. In their search for who should play Nick Young, they emphasized their need to find leading man material, but accommodated a standard that associates this quality with whiteness, and went halfway in the racial makeup of their lead.

It is also a very deliberate choice in the film to literally cut off Pierre Png’s head during his tantalizing shower scene, limiting our gaze to his torso and his body, as if to gradually accommodate the viewer to this idea that Asian men can be beautiful, through this initial encounter in which we cannot discern his race. It reminds me of the Asian men who put up headless torso profile pictures on various dating apps, using this racial ambiguity as a means of momentarily circumventing the racist gay gaze.

How does the film go beyond just being about heteronormative romantic relationships or normative family structures? Is there a queering of human relationships that the film effectively explores, and that queer POCs can relate to?

Queer critical scholar José Esteban Muñoz writes about how queer culture has always built itself around hegemonic straight culture and appropriates its elements for queer use. So, the queer value that I find in CRA comes from my gaze, and the power that queer people have to flip heteronormative icons. And in many ways, CRA is a queer movie because of the power this spectatorship has, making up for the lack of explicit queer content in the movie.

The queer value I most found is the real power in found family. It is about the kinship that Rachel builds with those who she is not directly related to, and how these allies she finds in her difficult situation support her throughout the story. This resonates with queer communities, because of how our birth families might disown or estrange us, leading us to create our own families out of exile. Such constructions are crucial for us on the margins, who must build up and move forward from positions of profound loss.

The feminist angle employed in the movie is an interesting phenomenon, especially because the source material comes from the voice of a gay male writer. What are your thoughts on how the movie explores a representational framework versus one employed by the book?

The book relied very heavily on camp and artifice. Camp scenarios flatten characters into heightened, cartoonish versions of how people actually act, especially for women, who are conceptualized by queer men as these highly-performative versions of femininity. In the book, the family’s matriarch, Eleanor Young, is a shrieking, villainous harpy, who is very externalized in her performance. In the movie, there is rich interiority in the way that actress Michelle Yeoh depicts Eleanor. A lot of the performance is very much implied, jarred within, held back, contained inside — it’s the subtleties, it’s what she’s not saying and not doing that makes her into a complex, three-dimensional person.

What CRA does is go beyond queering in the form of camp, into employing a representational framework. It is the interiority of these characters that representation aspires to, imagining in them a broadband of human experience as complex as those whom it reflects. Of course, there are many critiques of representational politics. Representation can threaten that these characters we see on the screen, due to the flatness of the surface itself, will inevitably harden into new stereotypes. But this only affirms that more images and representations need to be produced in order to continually decalcify this process.

Some people who haven’t seen the movie have expressed that they aren’t interested in something they can’t relate to–and they point to the storyline of Asians in Singapore. And yet the movie is very much about American narratives that are central to American and queer American experiences. What are your thoughts on how successful the movie is in exploring American experiences around being queer, or a queer POC?

I think it is a narrative that resonates with anyone who is estranged from a sense of home, and must reconcile the values of their newfound environments with their cultural roots. That lived experience in the film is not just about Asian Americans, Chinese Americans, or the global diaspora. It’s connected to the way we as queer people or queer people of color are unsettled from a sense of belonging in many respects, and navigate this tension between where we’re going and where we’ve been. Being queer is itself a kind of diaspora, in the way we are constantly outside of time and space. It’s the way that we can fashion belonging to the in-between that Rachel teaches us in the film, in face of structures that tell us to choose one or the other

Nico Santos plays Oliver T’sien in Crazy Rich Asians as gay friend. Photo: Kathy Hutchins/Shutterstock.com

In CRA, actor Nico Santos plays a character named Oliver who refers to himself as the rainbow sheep of the family. How does Oliver fit into the family structures and relationships in this movie?

There’s an easy reading that says he is a stereotype: the gay best friend or gay side kick that queer people have often been relegated to–one who doesn’t even get his own narrative arc. But there is a deeper complexity to the character that may be missed in a simple critique, and even a kind of performance that ruptures these stereotypes.

We could easily pigeonhole him as a fairy in the double sense of the word — a fairy godmother to Rachel, while also being fairy in the sense of the queer male trope. But there’s also the fact that by casting Nico Santos, a queer man of color himself, Oliver becomes much more than how he exists on paper and what he is scripted to be. The fact that Santos brings in his entire broadband of experience to this character can’t be discounted.

Speaking of stereotypes and social standards, there were several accounts from Asian American viewers noting that audiences–particularly audiences with mostly white viewers–reacted to the film’s meaningful wedding scene with a lot of laughter. What are your thoughts on that?

I went to several screenings of the film, where the audience was predominantly white–and yes, there was laughter during the wedding scene. I felt that this was so entwined with Orientalist dynamics. Humor and laughter come from dissonance. White-dominated racial constructions associate Asian-ness with a robotic quietness, sterility, lack of emotion, lack of feeling, lack of expressiveness, and inscrutability. This white racial construction of Asian-ness is incompatible with the wedding scene, which is actually a very romantic, maudlin experience and an extremely emotionally affective moment. The laughter was a manifestation of white audiences expressing a reaction to the juxtaposition of perceived mismatched parts.

The movie is marketed as revolutionary in a lot of ways. Do you think the movie is groundbreaking? And what can we do as Asian Americans and as POCs, to ensure that such representation continues in Hollywood?

What is queer survival versus queer revolution? Muñoz identifies how queer culture has made do, hinging on co-opting things from the straight world. But what if these retain, reinforce, and support the power structure of straightness and a straight-dominated world? And when do we tear it all down, instead? CRA is nice to have. It’s great to see ourselves on screen and reflected in these stories and in these characters. But I feel we should ask more from social change. Putting Asian faces in the extremely mainstream institution of Hollywood cinema is still a kind of compromise.

If you had carte blanche freedom to develop your own plot for the sequel to CRA, what would it be?

The ambivalence that I have about CRA is built into its very premise: on one hand it is personally empowering to have a story about Asian diaspora and Asian Americans, but on the other hand, it naturalizes the Chinese settler colonialism in Singapore. It’s really unfortunate that our identification with the characters and narratives in CRA is to the expense of those in the lower echelons of Singaporean society. If I had carte blanche freedom, I wouldn’t set CRA in Singapore, but in a Wakanda–a fictional Asian nation. Wakanda imagines a parallel universe in which an African country had resisted colonization. As such, the film was oriented as distinctly anti-colonial, in which identification with the characters was a punching up, rather than a punching down in the global power structure.